Introduce yourself

My name is José Guadalupe Olivarez aka Kola Champagne Papi aka Papi Churro aka Papi Two Times Two Times. I am a poet, educator, and aspiring sin vergüenza. My debut solo book of poems, Citizen Illegal, is forthcoming from Haymarket Books. I’m one of the hosts of a poetry podcast called The Poetry Gods. You can catch me at

joseolivarez.com or eating tacos at Coyotes in Pilsen.

Let us take it back three years ago to putting out your first book, ‘Home Court’. You were the co-author, alongside Ben Alfaro. How did you and Ben meet?

Ben and I have hella mutual friends. When I met him, we clicked right away. Right away it felt like we had been friends forever. I don’t remember how exactly we met, but it was probably at a Louder Than A Bomb Poetry Festival event.

After scrolling through the internet, I found one poem in the book. Page 233, the story on Oscar & Cesar’s dad dying. Talk a bit more about this poem.

That poem is called Home Court. I wrote it after going to a Junot Díaz lecture in Chicago. He had just released This Is How You Lose Her & he talked about one of the critiques of his work which is basically: Junot isn’t that good. All he does is cuss and write about sex. His response was about language. He was like I write for the guys I grew up with, so I use the language that they use. They aren’t necessarily going to reach for a book of feminist theory on their own, but maybe they’ll see these characters in my book that look and talk like them and hopefully, they’ll think about their own lives more critically. That answer helped me answer my own question which was: How do I write poems about intimacy, platonic love, & misogyny for young people (& specifically young men)?

I grew up with this very narrow conception of masculinity that didn’t allow room for excessive feeling. When bad things happened we were supposed to be strong and get over it. When good things happened, we were not supposed to get too excited. So I wanted to write poems that might have made it okay for a young person like me to feel.

After I heard Junot talk, I was like what if I try to write poems of emotional depth using the language of sports. Home Court was the first poem I wrote in that series and became the title poem of the book Ben and I wrote together.

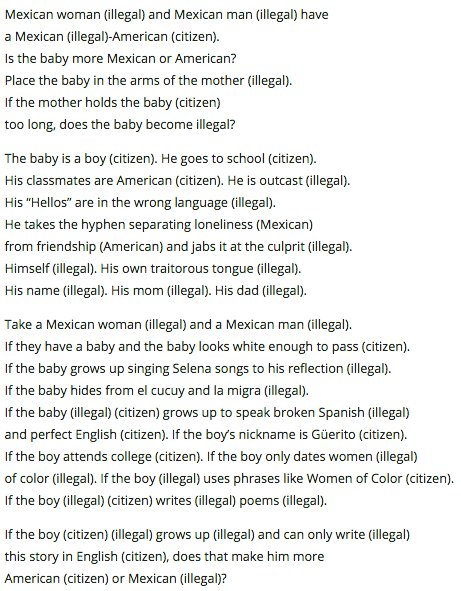

This year you put out a poem titled (Citizen) (Illegal). You recently announced that you’re putting out your new book called Citizen Illegal with Haymarket Books. Was that the rollout plan?

Nah. I wrote that poem as early as 2014, I think. I showed it to my friend, Nate Marshall, & he was like that should be the name of the book. I didn’t have a book written, but Nate was right.

Did this poem inspire your new book?

Not exactly. You’ve heard people talk about writing the book people want to read themselves? That’s what I was trying to do. I wanted to write the book that I needed to read as a young person. The book that might have helped me heal a little more in my early twenties. Citizen Illegal is important to the book. It’s the title poem, and it is one of my favorites from the collection because it shows different ways that identities stack and stretch. It asks questions about power. I’m thinking a lot about power.

What can we expect from this new book?

Citizen Illegal is not a book of translation. It is not meant to be a guide to understanding Mexican American life. It’s not meant to decode such mysteries as how do Mexican mothers turn chanclas into aggressive weapons. It’s a book of poems that are meant to show and give voice to the ghosts and joys that haunt Mexican life. It’s also a hella midwestern book. This is a steel mill book. This is a move to the suburbs and they’re foreclosing all the houses book. This is an economic crisis book of poems.

What’s your favorite poem in Citizen Illegal?

My favorite poem is called Mexican Heaven. It’s forthcoming from the Adroit Journal, so you’ll be able to read it soon. It’s a poem that reimagines heaven in the tradition of a poem like Natalie Diaz’s “Abecedarian Requiring Further Examination of Anglikan Seraphym Subjugation of a Wild Indian Rezervation.” St. Peter is in the poem, but he’s a Mexican named Pedro and sometimes he drinks too much.

Let us talk about two of your favorite poets, Gwendolyn Brooks and Lucille Clifton. Why are these two your favorite?

I grew up writing in the tradition of Gwendolyn Brooks. The first writing mantra I was given was when Kevin Coval told me to write the stories under my nose. He took that from Ms. Brooks. It taught me to look my own life and my neighborhood and my family to write poems. Her work is so filled with lush imagery, and gorgeous turns of phrases, and a precision that still inspires me to this day. Read A Song in the Front Yard. Read When You Have Forgotten Sunday: The Love Story. Read my dreams, my works must wait till after hell.

Lucille Clifton is great. Her poems teach me about the great distances that poems can travel in a short amount of time. Her poems are usually pretty short, but there’s not a mightier poet. Funny too. I return to her work pretty frequently. won’t you celebrate with me is one of my favorite poems of all time. It’s an anthem to hold on to. Read 1994. Read blessing the boats.

On top of being a writer, you’re a teacher at YCA, where you came up writing as a young kid. How important was it for you to give back and teach the next generations of kids at YCA? They always say teachers help the students learn, but how much have you learned from the students while teaching?

I’m going to combine both these questions and hopefully, this makes sense. Teaching is not separate from my writing. These are both creative ways that I can contribute to my city and my people. When I write poems, I am reaching out to the same young people I teach in workshop. The poems and songs and videos and questions I bring to workshop are the same things that inspire me. Teaching is a part of my writing practice.

I’m also thinking here of lineage. I’m thinking about my mom teaching me my alphabet by making me watch Sesame Street with her. I’m thinking of Ms. De Jong writing a letter of recommendation for me, so I could go to college and sharing her favorite books with me. I’m thinking about Mr. Mooney telling me my first poems were very bad, but if I wanted to learn I should keep showing up. I’m thinking about Sandra Cisneros and how without her work, my work would be impossible. I’m thinking about Erika L. Sánchez and Jacob Saenz and Eloisa Amezcua. Their work continues to make my life possible. You know what I’m saying? When I started learning English, an elementary principal told me the only place for me in his school was in the special education classroom. It is impossible that I am a writer. & yet, here I am. So I’m not thinking about giving back. I’m thinking about the future. I sit in classrooms with my students, who are almost all POC, and I know that it is impossible that they are sitting here writing poems to each other. Like, history would say nah to my students. The past never considered us, but here we are, so how can we create a future that feels more possible for young people of color, for queer people, for women, for gender fluid and nonbinary people, for trans people, for people everywhere living on the margins? That’s what I think about when you ask me about teaching.

When it’s all said and done how would you like to be remembered?

I would like to be remembered as kind and generous. I suppose that I’m scared of growing stubborn, so I hope that 50 years from now when a young poet reaches out with work that is so far removed from my own practice that I still listen to them and are open to their work. I hope I never stop learning.

Thought provoking

LikeLike